How aware are we of how we’re feeling day to day? Or more importantly, why we’re feeling that way? For many men, those ideas remain a mystery well into adulthood. We only rarely tune into our emotions, and even then it can be difficult to understand what our body is trying to tell us, beyond, perhaps, mental flash cards reading “stress” or “anger.”

“Emotions are neurochemical feedback loops. They’re your brain’s way of making sense of internal and external experiences,” says Chris Meaden, a trauma, anxiety and phobia therapist whose work involves working directly with the amygdala — the brain’s fear center — to create lasting emotional change at a neurochemical level.

As Meaden explains, emotions are not random phenomena, but signals designed to inform and guide our behavior. “Think of them as your internal warning system or compass, not something to push down or ignore,” he says. “Every emotion exists for a reason, and it’s often asking you to pay attention, not to panic.”

Emotions are essential to the human condition, and always have been. The issue, according to Meaden, is that our relationship to them has changed. In a hyper-stimulated, fast-paced world, too many of us are disconnected from our body and emotions. We’ve learned to override or suppress feelings rather than listen to them.

“That’s the survival brain kicking in,” says Meaden. “When your nervous system detects even a perceived threat, the amygdala fires up and sends a ‘get safe now’ signal.” This might look like anger, withdrawal, defensiveness or shutting down. These aren’t conscious decisions — they’re rapid, automatic protective strategies that evolved to keep you alive.

“The challenge today is that the threats aren’t lions anymore; they’re emails, conversations, memories — and we’re still reacting like we’re in the jungle,” says Meaden.

Where Do Emotions Come From?

If we’re going to react more favorably to our emotions, it helps to understand where they’re coming from and what’s going on within us at a physiological level. While emotions can overlap, neuroscience shows that different emotions engage different circuits in the brain.

Fear and anxiety are rooted in the amygdala and limbic system, Meaden explains, triggering adrenaline and a fight-or-flight state. Sadness engages areas like the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which are often tied to reflection and memory. Stress, especially chronic stress, involves the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which keeps the body in a loop of high alert.

“Each emotion carries its own chemical cocktail,” says Meaden, “which is why they feel so different and drive different behaviors.”

The Analog Life: 50 Ways to Unplug and Feel Human Again

There’s life beyond the infinite scroll. We put together a toolkit of habits, routines and products to help you live more intentionally.How to Deal With Different Emotions

Knowing that emotions are essentially chemical reactions in the body, Meaden says it’s possible for men to cater individual responses to how they’re feeling. This takes a lot of work. But next time you’re feeling off and you’re able to recognize a specific emotion or two you’re feeling, you might try a practice called “Havening.”

“[It’s] a neuroscience-based technique, which uses specific soothing touch (on the arms, face or palms) to change how the brain encodes and stores emotional experiences,” says Meaden. “This generates delta brainwaves — the kind your brain uses during deep sleep — and helps deactivate the amygdala, reducing stress chemicals and creating a sense of calm and safety.”

Meaden uses this with clients recovering from PTSD, panic attacks and other emotionally overwhelming experiences. He says the results can often be dramatic. Here’s his advice on how to deploy the tactic for four specific emotions:

- Stress: “Stroke your arms from shoulder to elbow, rub your palms together or gently sweep across your forehead and cheeks. This [Havening] calms the nervous system and lowers cortisol within minutes.”

- Sadness: “While using Havening, add in gentle, self-supportive phrases like ‘It’s okay to feel this,’ or ‘This too shall pass.’ This activates your prefrontal cortex and begins to shift the emotional weight.”

- Anxiety: “Use Havening while visualizing a calm, safe place or repeating, ‘I am safe now.’ This interrupts anxious looping patterns and lays down new neural associations.”

- Fear: “Pair [Havening] with imagery of someone you trust, or a moment you felt secure. The brain can’t tell the difference between real and vividly imagined safety — this tricks the fear center into standing down.”

What About Anger?

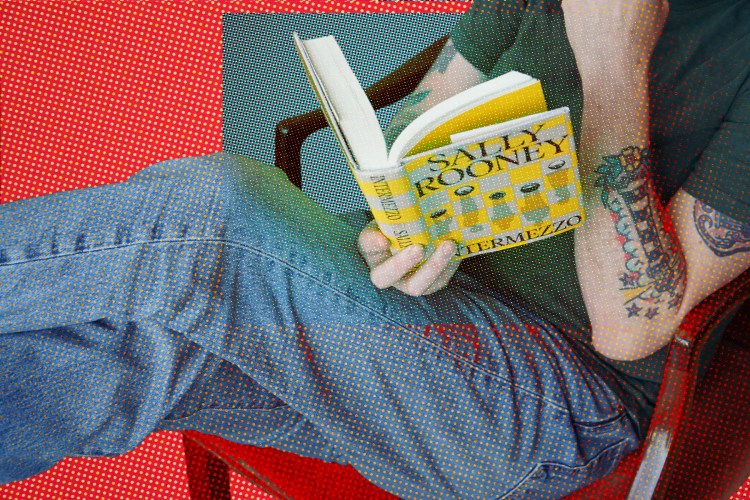

Anger, which activates the hypothalamus and motor cortex, gearing the body up for action, is arguably the last taboo in the field of emotion. Sam Parker, a British editor who has written and edited at Esquire, GQ and the Observer, has written on exactly this in his forthcoming book, Good Anger.

“I think anger is misunderstood in lots of ways,” Parker tells me. “We think of it as this uncouth, barbaric, shameful emotion that’s there to trip us up. In fact, it’s there to protect us and alert us to boundaries that have been crossed, or deeper issues we need to face.”

“Most of the time, anger has something to tell us about ourselves,” he notes. “We have a wound we’ve ignored or an unmet need or an area of our lives where we’re not confident or secure yet.”

In Good Anger, Parker seeks to “dismantle what I thought I knew about anger and start again.” He does this by investigating his own anger, that of his friends and colleagues, and traces the history of how it became such a taboo emotion. There’s even evidence that unreleased anger can lead to physical problems including autoimmune diseases, cancer, an inflamed nervous system and even rheumatoid arthritis.

“We need to get away from framing emotions as feeling positive or negative in a particular moment and start thinking of them as what they are: information,” psychologist Ray Martin told Parker. Couldn’t we all do with more of that?

How Do I Deal With My Anger?

Like any emotion, recognizing anger can be trickier than it seems. For Parker, anger often came with other emotions, and was sometimes masked by them. Often, for example, we might think we’re anxious when a good chunk of what we’re feeling is anger.

“For me, the first challenge with anger was primarily one of identification,” Parker writes. “I found it hard to know it was even there, unless it became dialed up to 11. Often, I’d get distracted by some other emotion pretty quickly: fear (over what anger could lead to) or apathy (a sense that it was all pointless anyway).”

To put his anger to good use, Parker realized that he needed to be able to recognize it clearly, “without denying it or calling it something else”. Therapy can help with this, as can realizing that anger does not always equal violence and aggression. Feeling angry is fine — beneficial, even. But lashing out is the opposite.

“Try narrating the experience in real-time,” advises Meaden. “For example: ‘I notice my jaw tightening…I can feel heat rising in my chest…I’m starting to feel angry.’”

Meaden says that this tiny shift — naming instead of reacting — moves activity from the limbic system to the prefrontal cortex, giving you more control in the moment. It sounds simple, but it’s a powerful way to re-engage your thinking brain before things escalate.

For Parker, boxing became a reliable way to channel his physical feelings, but it wasn’t the solution. Rather, it gave him space to consider his unexpressed feelings of anger and where they might be coming from. With this mental clarity, he was then able to take steps to address the underlying issues.

Instead of counting to 10 or waiting for your anger to pass, channelling it physically can deal with the energy in your body, while giving your mind time to react in a helpful way. Don’t worry if boxing isn’t your thing. Maybe you like to dance. Or cycle. Or play the guitar really loudly.

Whatever you do, and whatever emotion you’re dealing with, don’t skip the most important part: actually taking time to listen to what your emotions are trying to tell you. After all, as Parker writes, “We are at our best when emotion and reason are working together.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.