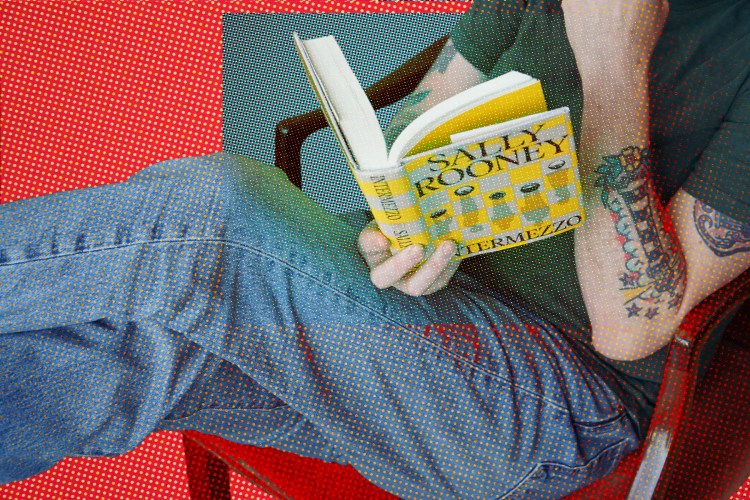

The experience of watching a memorable film can be transformative, but who you’re watching it with can also shape how that goes. While there’s plenty of great writing about films themselves, there’s also a growing body of work dedicated to the actual experiences of moviegoing. Quentin Tarantino’s recent book Cinema Speculation is one example of a dedicated cinephile going deep on the experiential aspects of the movies; Ben Tanzer’s new After Hours: Scorsese, Grief and the Grammar of Cinema is another.

Tanzer’s book focuses on Martin Scorsese’s 1985 cult classic while also factoring in the author’s experiences of watching it while growing up. For Tanzer, the film gave him a window through which he could reflect on his relationship to his family and chronicle the aftermath of his father’s death.

“I saw this as an opportunity to explore the intertwined themes of creativity and grief, the most omnipresent themes in my head beside paying bills and trying to be a present parent, husband and brother,” Tanzer said in a recent interview with New City Film. In this excerpt from his book, Tanzer revisits the circumstances behind the making of After Hours and charts them against the arc of his own life.

At some point in the 1990s — well after After Hours was released in 1985 and somewhat after Goodfellas in 1990, though well before The Departed in 2006, which is not bad, The Wolf of Wall Street in 2013, which is quite fun, and The Irishman in 2019, which I enjoyed — I asked my father what we should make of Scorsese. Which is to say whether he thought he was done creating the kind of transcendent work we loved. My father responded, “how many masterpieces does someone need to make?” We didn’t discuss what my father considered Scorsese’s masterpieces, though I knew for both he and my mother it was Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980). Goodfellas and The King of Comedy (1982) were also part of the conversation. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) didn’t quite fall into this debate, though my parents both found it powerful and important — even if my father couldn’t quite get past Harvey Keitel playing Judas with a Brooklyn accent.

Still, The Last Temptation of Christ is crucial to any discussion of After Hours. As described in Esquire upon the thirty-fifth anniversary of After Hours, “there was a time back in the early 1980s when Scorsese was written off as box-office poison.” As Scorsese himself says in the article, “I had the TV on in the background, and for some reason it was tuned to Entertainment Tonight. And I heard them say as sort of a tease before they went to commercial, ‘Coming up: The Movie Flop of the Year!’ So I sort of stuck around to see what it was. What was the Movie Flop of the Year? And when they came back, they said it was The King of Comedy! I was the flop of the year! And on top of that, I had been planning to make The Last Temptation of Christ, which had just been canceled on me. So it was a double whammy. I had nothing lined up next. And I knew I was going to have to start all over.”

Scorsese’s next movie after the “flop of the year” would be After Hours.

~

After Hours is about the desire to escape the cubicle life: meaning structure, stability, predictability. I didn’t grow up like that. In my house, there were no rules — or not many — or expectations, beyond being a decent person, becoming an activist and seeking out work — always work. My parents were people engaged with the world and focused on their relationship, art and travel. They weren’t always present, but there wasn’t much for me to escape from. On Friday nights, we would eat dinner at Little Venice Restaurant in downtown Binghamton, New York, where I grew up. Those dinners were followed by us going to the movies. As I got older, we watched movies together less often, though I was still likely to see films they recommended. These included:

The King of Comedy.

Little Odessa. My father recommended it, though my mother believes she did as well. Anyway, it was New York City and Russian Jewish mobsters, and my dad loved New York City and mobsters. Years later I met James Gray, the writer/director of the movie, and when I told him how much my father and I had enjoyed it, he replied, “And you’re the only two people who’ve ever seen it.”

She’s Gotta Have It. My father had a habit of seeing movies before I did and telling me to see them. He liked this one and made sure I knew it.

The Shining. I loved Stephen King’s books then and loved this movie — not that Stephen King did. It doesn’t speak to my experience as a writer, though it didn’t scare me either. I consider that a win.

Body Double and Body Heat. The latter starred the still young William Hurt and Kathleen Turner, as well as Mickey Rourke and Ted Danson. Body Double stars Melanie Griffith and Craig Wasson. Both are about obsession and anything about obsession is good with me.

One False Move. So much violence and dread, plus Billy Bob Thorton and Bill Paxton.

Something Wild. More Melanie Griffith and more violence. It also co-stars Ray Liotta in a truly incendiary breakout performance.

And of course, After Hours.

Everything Martin Scorsese Has Ever Done, Ranked

From the classic films to TV shows, ads and shorts, we rated all things Marty~

A key conceit to After Hours is the sense that it could only happen in New York City. Especially during the 1980s, the city was the perfect mélange of weirdness, dislocation, art and potential violence. However, I was never scared of New York — in part because I wasn’t raised to fear the city. In the 1970s and 1980s, my parents and I would visit my grandmother in Queens, where we ate chopped liver on Ritz crackers. We went to see Broadway shows — including the original runs of Grease and Sweeney Todd. I attended my first professional baseball game at the original Yankee Stadium, mere blocks from the neighborhood where my father grew up. These are childhood memories, though. I also lived in the city as an adult from 1992 to 1994. I have numerous reminiscences from those years too, including:

• Tripping on mushrooms at Webster Hall on East 11th Street, then walking the empty streets and being passed by a pack of rats — who then beelined down a deserted alley.

• Having drinks at the original Max Fish on Ludlow Street after being informed beforehand that if we took the correct turn of the train, we’d easily find it and if we took the wrong turn we’d walk into a drug deal. We took a wrong turn, and yes, walked into a drug deal.

• Eating pâté in the early morning with the queens and club kids at Florent in the Meatpacking District on the way home from wherever we were and not yet ready for bed.

•Hitting CBGB to watch Monkey Wrench fronted by Tim Walikas, a friend of mine since middle school.

• Getting home late one New Year’s Eve to an answering machine message that we were invited to a party Parker Posey was also attending. The message was from Adam Lawrence, another childhood friend of mine, who knew her from college.

• Volunteering at Gay Men’s Health Crisis to raise money and support for the AIDS Walk and HIV/AIDS research and programming.

• Discovering the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat at his first post-death retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

• Feeling terrorized by a neighbor on West 96th Street who wandered the building and our neighborhood with a hunting knife and pit bull whose mouth was sealed with duct tape. He would eventually blow up his apartment, which he told the police I was responsible for, and set our building’s elevator on fire.

• Working in Long Island City during the first World Trade Center bombing and watching the smoke ascend into the sky from my office window.

• Getting assaulted on a sunny Friday afternoon on West 125th Street in Harlem — the entire incident lasting two minutes, the scar which bisects my eyebrow permanent.

~

From 1990 — when I graduated from college — through 2016, I worked 9 to 5. While I was never quite an office drone, I did work in offices, with bosses, trainings, human resources, supervision, repetition, interviews, salary negotiations, cubicles and private offices, countless co-workers — some good, some bad, most indifferent — endless meetings, retreats, conferences, planning sessions, expense reports, invoices, fights, hotel rooms, per diems, and on and on. I craved structure, stability, regular paychecks, health insurance and retirement plans. I was never quite Paul Hackett, yet my life was much closer to his than that of my parents. My father worked at IBM for one day in his early 20s and never entered an office again. My mother worked in a mental health clinic when we first moved to Binghamton, but it didn’t stick, and she went into private practice. She ascribed this decision to poor management at the clinic, though this doesn’t change who she is, or my father was — people who followed rules yet needed to make their own, and who sought comfort, but not at the expense of forging their own paths, which were unrestricted and well outside the confines of institutions. I wasn’t that guy. I may not have been Paul Hackett, but for many years I felt more trapped than I cared to admit.

The above is excerpted from After Hours: Scorsese, Grief and the Grammar of Cinema by Ben Tanzer, published by Ig Publishing on May 6, 2025.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.